| Search God Save The Sex Pistols with freefind |

|

REVIEWS BOOKS - ARCHIVE Includes;

Satellite, Vacant, Rotten, 12 Days On The Road, England's Dreaming, The Wicked

Ways Of Malcolm McLaren, I Was A teenage Sex Pistol, Lipstick Traces.

(Review

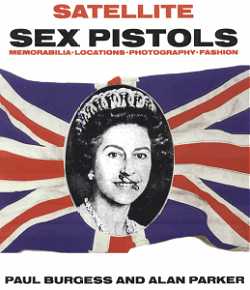

and interview from Record Collector No. 241, September 1999) The authors of this new work, Paul Burgess and Alan Parker, are certainly qualified to carry out the task in hand. Parker is a punk enthusiast who has contributed to your very own Record Collector, as well as finding the time to pen the best-selling book, Sid’s Way, Burgess, on the other hand, possesses all the attributes required to provide a visual Sex Pistols feast — after leaving the Royal College of Art with an MA in 1986, he has spent the last thirteen years as a successful designer and photographer, best known in the UK for his illustrative work. He also has another mandatory qualification:he is an avid Pistols fan and punk collector. You’re probably asking yourselves why on earth we need another book on the Sex Pistols. After all, their short but turbulent career has been chronicled endlessly, and surely everyone knows all there is to know about the godfathers of punk? Alan Parker explains: "Between us, Paul and myself probably own every single Sex Pistols book, and we felt it was about time there was one that we’d like to go out and buy. You can spend so much money on Pistols books only to usually find out that a mere five out of the ninety pages you’ve bought are of any use at all. What our book does that none of the other titles do is to actually put everything on show. The Jon Savage book, England’s Dreaming, is awfully good if you just want to read, but while it’s one thing reading about a particular T-shirt that McLaren almost finished, it makes you even more curious to actually see it! And that’s the role that this book fulfils." Paul echoes this sentiment: “We wanted to visual companion to the other books there so that people could read the story and then pick up our book and see everything referred to in the others. We didn’t want to put anything in it that had appeared in other books. I’ve actually designed the layout myself so that the book corresponds directly with our ideas of what we wanted to see as well.’ Satellite is divided into four distinct sections: Memorabilia, Locations, ‘Photography’ and ‘Fashion’. Each is copiously illustrated with items ranging from the bizarre - the 1996 reunion Sex Pistols promotional phone-box prostitute cards - to the more mundane, such as Westwood and McLaren-designed T-shirts, gig posters and press kits. On top of this, it also contains a comprehensive discography and a complete list of every gig the Pistols ever played, as well as a guide to collector’s outlets selling Pistols-related memorabilia. With such a wealth of information, it seems incredible that the book was compiled over the space of just one year! A lot of the memorabilia is either Paul’s stuff or mine,” explains Alan. “But we’ve also been really fortunate because Paul’s got some good mates — Paul Stock and Andrew Wilson — who own a big clothes collection. They’ve held a few exhibitions and they’ve lent us everything they have to put in the book. Another reason we’ve been lucky is that we’ve both been collectors for so long, we’re well in with all the other collectors. The ‘Locations’ section of the book was probably the hardest to research. There have been similar books dedicated to the Beatles and we thought the idea had been done to death, but we then realised that there are a lot of landmarks in London that relate to the Pistols that people maybe weren’t aware of. Of course, that meant Paul and myself had to go around to all these places and find out as much as we could about them. McLaren’s old office is now a sports shop where they sell football strips and the like, so we were stood across road going ‘I wonder if that’s it’?’ As well as a remarkable display of Pistols memorabilia, the book also showcases a large number of previously unpublished photographs. “When we initially planned that section, we were quite nervous,” says Alan. “We didn’t think that there actually were enough unpublished photos to fill it. Paul had been to the Rex Features photo library and a few other places and came back with tons of pictures which we had to whittle down to an affordable and sizeable number to fill that section. I think we’ve done well as there are pictures in there that I have certainly never seen before. I think that the picture section might shock a few people, especially those who have been used to buying photo books featuring the same material over and over again. We’ve got an excellent shot of Steve and John sat backstage each with a bottle of lager, which we’ve blown up to a double-page spread. Then there’s a fabulous one of John and Steven Fisher - the Pistols’ solicitor - outside court in 1977, and John’s wearing a suit!” Of course, as with any endeavour of this nature, it was never going to be possible to catalogue and display everything related to the Pistols. Paul explains: “I spent a lot of time going to see people who worked with the band at the time, so I borrowed and begged a lot of clothes and photographs. However, we’ve found even more since the book’s been finished! I went to see Helen Wellington-Lloyd - the dwarf in The Great Rock & Roll Swindle - yesterday, and she’s got suitcases full of original artwork and the like. The more people we meet, the more we’re seriously thinking about doing a second volume.” Nevertheless, there’s plenty in the book to surprise even die hard Pistols collectors, including Glen Matlock’s original hand-written lyrics for ‘Pretty Vacant”. What’s particularly surprising is the fact that the book is almost officially approved: “We haven’t shown it to many people, but those who have seen it haven’t said a bad thing about it. And some pretty important people have seen it. Some of the people who used to work for McLaren have seen it and Paul showed a copy to Glen (Matlock). Last night at his gig we were handing out flyers for the book, when somebody asked, ‘What’s it like?’ Without any cue from us, Glen turned round and said, ‘It’s fantastic, mate. You should get yourself one!’ So, there’s approval for you!”

Satellite

is published by Abstract Sounds Publishing I know this isn't a very fashionable thing to say but punk was shit. An overblown collection of smackheads trying to find some kind of mass personal identity, attempting to be individuals and walking around looking like Grotbags the witch. Moody-looking birds and bantamweight, muscleless freaks with no talent who somehow managed to inspire a witless musical movement that revolved around being rude. l've got no problem with Iggy or the Sex Pistols, maybe even the Misfits, but it should never have gone further than that. You want to be an individual, don't travel around in herds. And if you old punks don't like what I've just said, you probably weren't much of a punk in the first place. Anarchy! My daddy's chairman of BP! Piss off. By the way, the book's got lots of nice pictures in it so you can spot all your old middle-class Tarquin mates dressed like shit to upset mother. 10/10 Review, Phil Robinson - Loaded. June 1999 Ray

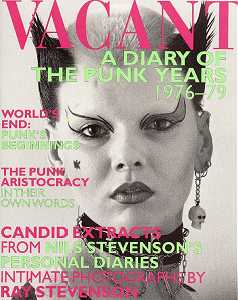

Stevenson - Vacant www.photos.fsbusiness.co.uk/

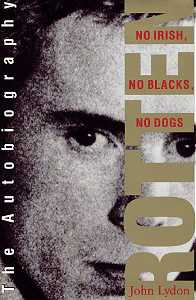

Even now, a decade and a half after everything felt apart, the story of the Sex Pistols is well worth telling as a corrective to anyone who fancies the pop animal to be a docile and malleable beast. The outlines are these. Two working class delinquents (Steve Jones and Paul Cook) and an art student Glen Matlock) hook up with a maniacal north London teenager named John Lydon, soon rechristened “Rotten”. Under the tutelage of a canny entrepreneur (Malcolm McLaren), who has read the biographies of famous pop impresarios form Larry Parnes down, they form a band. Success - add notoriety - come in a matter of months, fuelled by yellow-press hysteria, televised profanity and the stirrings of a noisome youth movement, but it is an odd kind of success. Propelled by McLaren’s unflinching aptitude for annoying people, the Pistols acquire their reputation by failing to do most of the things that conventional pop groups do, ie, by not touring (by any 1977 scarcely a municipality in England would let them through the town gates), and by being paid huge sums of money not to make records. Those that do creep out are attended by maximum controversy and maximum sales. Almost immediately, though, the Pistols blow it. They make the fatal mistake of firing the one person who knows anything much about music (Matlock) and replace him with someone who merely looks the part (Lydon’s chum, Sid Vicious). McLaren, by this time is more interested in film-making (what will eventually crawl out of the can as The Great Rock ‘N’ Roll Swindle), is storing up trouble by diverting most of the band’s advances into celluloid. Finally, after a catastrophic US tour early in 1978, everything falls apart. Sid, having apparently murdered his American girlfriend Nancy Spungen, kills himself. Jones and Cook go off to be ex-rock stars. Lydon returns, eight years later, to take McLaren to the high court and the cleaners: McLaren settled out of court for nigh-on £1m in back royalties. By this late stage in the proceedings, nearly everyone involved in this breathless two-year flurry of noise, death and outrage has had his or her say. Hangers-on and managerial accomplices have written up the tour atrocities in their usual affectless way. Matlock, with the aid of a nimble ghostwriter, has produced his own account of injured innocence, I Was A Teenage Sex Pistol, and there have been a number of attempts, notably Jon Savage’s somewhat overwrought England’s Dreaming, to weld the Pistols’ brief career into an apocalyptic social and political context. The least that can be said of Lydon’s version - and it would be stretching things to call this collection of transcribed tapes, affidavits and sidekicks’ testimonies a book - is that it is no more self-serving than anyone else’s. And no less. The themes of Rotten have a convenient unity: it was me; I did it; they were my ideas; Malcolm and Vivienne (Westwood) ripped me off; never trust a hippy (Richard Branson), and so on. Now in his mid-thirties, the old boy hasn’t mellowed an inch. For the second time in 17 years. Matlock is told that he can drop dead, the mention of McLaren’s name inspires an almost audible grinding of teeth, and the finished product shows every sign of having stalled for months on the desk of Hodder’s legal adviser. There is another agenda here, though, aside from self-justification and denigration. “We were teenagers making teenage music,’’ Lydon suggests at one point, which is a welcome response to the egghead theorising about situationism. At the same time, much of the controversy surrounding the Sex Pistols grew out of Lydon’s confrontational lyrics. The social and even personal hatred that seemed to stare out of their live shows was unprecedented - and Rotten’s first TV appearance - unblinking, detached face caught up in a rictus of loathing - quite horrifying. There is a lot more of this in this book - musings about Her Majesty and public schoolboys - and the effect is just awful, like listening to Lennon on God, or Morrissey on practically anything. Oddly, or perhaps not so oddly, the best part of this “authorised autobiography” (was there ever an unauthorised autobiography?) has nothing to do with the Sex Pistols or even with Lydon’s strictures on the Establishment. If Lydon has anything to say about anything, it is about a priest-haunted Catholic childhood ground out in the tenements of North London. Lydon’s early life in a brooding, cantankerous Irish family in Finsbury Park was clearly a Gehenna of deprivation, if leavened by human warmth: friends attest to the squalor of the Lydon domicile, but also to the genuine affection of the Lydon parents. When Eileen Lydon lay dying, her son sat at her bedside for 10 weeks. School, education, the entire mainstream world in fact, was no more than a kind of hopeless chimera. The message, consequently, is the familiar message about channels of working-class advancement, and the failure of the state educational system to stir any kind of response in most of the people under its care. The parallels with a performer of a slightly later vintage, such as Morrissey, whose early career was sedulously exposed in Johnny Rogan’s 'Morrissey And Marr: A Severed Alliance', are striking: the Irishness, the strange, fractured intelligence, the same interest in writers such as Oscar Wilde, the same absorption in the iconography of the state. Both men are fascinated by the royal family, and the connection between Lydon’s sneering God Save The Queen and The Smiths’ The Queen Is Dead scarcely needs to be stressed. Lydon is allowed to call Her Majesty a “f—ing hard bitch”, by the by, which is ironic in a book that discourses so knowledgeably on English repressiveness and the denial of free speech. The rest, inevitably, is score-settling of a peculiarly rapt and obsessive kind: he digs at Matlock (for wanting to write pop songs and for fearing that his mother would be upset by Lydon’s lyrics); Alex Cox (for the Sid And Nancy biopic); Sid (for being thick and impressionable); McLaren (for everything). Ominously, the worst of this contempt is reserved for Nancy Spungen, Sid’s inamorata, and a horribly reliable scapegoat for What Went Wrong. There cannot be many more evil destinies than to wind up dead at the age of 20 under the sink of a seedy New York hotel room and then, 15 years later, find yourself memorialised as “vile, worn and shagged out’’, ‘‘a beast’’, or (this from Chrissie Hynde of The Pretenders), “It wouldn’t have surprised me if Sid or anyone had killed her, she was that obnoxious.” (Lydon, it transpires, had already tried to pre-empt Sid by rubbing dirt on the end of Nancy’s needles.) As may perhaps have become apparent by now, this is a vain, idle and only obliquely revealing book, full of wonderful printing errors, contradicting itself from page to page, and apparently aimed at the type of mid-Atlantic purchaser who needs to be told that Heathrow Airport is in London, and that you travel into Oxford Street on the subway. Lydon makes huge claims for his music (and his father is brought in to assert that “my Johnny changed the world”) without submitting them to any kind of sustained scrutiny. The Sex Pistols’ legacy, apart from about seven classic songs - their recorded output is pitifully sparse - was to create the market conditions in which a new breed of pop performers, few of whom had much to do with punk, could succeed. However, as Lydon seems to loathe virtually all living musicians, this is not a point he is ever likely to concede. In the end, the unanswered questions are not musical or cultural (the distinctions between various late 1970s youth groupings are painstakingly set out), but personal. What does Lydon really think of Sid Vicious, whom he formed in his own image and then abandoned to Malcolm, Nancy and heroin? What was his real relationship with McLaren, who has plausibly suggested that Lydon’s fury proceeded out of pique at being paid insufficient attention. As Lydon himself put it in one of his best songs, ‘‘There’s no point in asking: you’ll get no reply.” Review, D J Taylor – The Sunday Times. 10th April 1994

'Under the table with Johnny' ROTTEN:

No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs THE smell of cordite pervades No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs (Hodder & Stoughton £14.99), the memoirs of former Sex Pistol John Lydon, who, as Johnny Rotten, more than anyone embodied punk’s contradictions — apathy and energy, anarchy and engagement, safety pins and fashion sense. Loathed by the rockocracy he threatened to topple, by monarchists incensed by ‘God Save The Queen’, by tabloids, Tories and puritans, the Pistols and punk were the antidote to the jingoism and deceit of 1977’s Jubilee year. Though often fascinating, Lydon’s is inadequate as an account of one of British pop’s greatest moments. He is no writer, and the taped monologues that constitute his text are poorly transcribed and repetitive. Review, Neil Spencer - The Observer. 17th April 1994

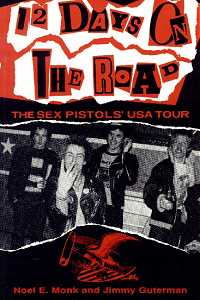

By the time The Sex Pistols touched down in America in January 1978, it was all over, bar the shouting headlines and the posthumous merchandising. In a little over two years they had become the crazed and depraved creatures Malcolm McLaren often said they were and certain sections of the British media always wanted them to be. The monstering process started when the foursome allowed Bill Grundy to goad them into a bout of yobbish swearing on television, three weeks before Christmas 1976. It gathered momentum two months later with the sacking of the most conventionally musical group member, bassist Glen Matlock, in favour of a psychotic teenage ingénu who called himself Sid Vicious and couldn’t really play. The various bannings and violent physical assaults The Sex Pistols attracted throughout 1977 completed the damage. Despite recording an album, Never Mind the Bollocks, which conclusively demonstrated the remnants of a fiery resolve and a subversive intelligence, the group had ceased to be viewed as a musical phenomenon some months before it came out. Anarchy was their slogan but notoriety became their obsession: as so often happens with young pop stars, the Pistols began to believe their own hype and, worse still, act up to it. Provocation had given way to loutishness. Bottles of lager and V-signs were as much their visual trademarks as spiky hair and bondage trousers. Vicious and his American girlfriend Nancy Spungen had already been arrested once for drugs, and their relationship, which increasingly revolved around mutual mutilation and a shared infatuation with injecting heroin, was undermining what little band unity had survived McLaren’s cynical manipulations. Music was almost a sideline. Apart from an idiotically tasteless contribution from Vicious, Belsen Was A Gas, no new songs had been written since the recording of the album in the summer. Concerts usually had to happen in secret venues under assumed names. Though Johnny Rotten and the guitarist Steve Jones still took the idea of performance seriously, and drummer Paul Cook could still keep the beat, Vicious was seldom in a condition to do anything except prance about and make himself bleed. The Sex Pistols were now a horrific cartoon of their former selves. And so to America, where their local tour manager Noel Monk, assisted by rock journalist Jimmy Guterman, takes up the pathetic tale in 12 Days On The Road. There is, alas, not a lot to tell. Though the short tour was designed to be as confrontational as possible, homing in as it did on club venues deep in the heart of Southern redneck territory, America seems to have been surprisingly tolerant of The Sex Pistols. A few threats of violence were received but never carried out. The photographs in the middle of this book, portraying fresh-faced fans dressed in flared jeans and platform-soled shoes, suggest that to many American girls the Pistols were just another English rock band. Outside the metropolitan hipoisie on the two coasts, their attempts at being outrageous probably looked rather quaint. The most significant event in Monk’s story concerns the break-up of the band after a show in San Francisco. McLaren wanted to fly the group to Rio to cavort about with the train robber Ronnie Riggs. Rotten read this as an attempt to sack himself and refused to go. Monk reports a brief conversation during which Rotten said he was “bloody well fed up and disgusted” and that the band was over. Revelations of this nature do not of course, sell books. Sordid tales of drug addiction do, though, and Monk and Guterman have spared no effort in assembling material about Sid Vicious. Much of it is so revolting and/or pornographic that it defies summary: suffice to say that, by this account, Sid spent his 12 days in a haze of heroin and peppermint schnapps; sex and self-inflicted wounds were his chief recreations; shooting up and throwing up his daily rituals. He couldn’t keep any food down and wouldn’t wash, Monk reveals. By the time he overdosed after the San Francisco show, Sid’s body was a mess of festering cuts and needle marks. The wonder is that he survived for another year. After even the briefest exposure to a book like this, you want to wash your hands. If you make it through to Guterman’s final hypocritical figleaf of an apologia, you feel quite sick. “The Sex Pistols recorded some of the most thrilling music in all rock and roll,” he writes. “Not even the vast amount of cynical exploitation that has arisen in their wake can undermine that.” Well, he should know. Robert Sandall is the rock music critic of The Sunday Times Review, Robert Sandall – The Sunday Times. 14th June 1992

ENGLAND'S DREAMING Sex Pistols and Punk Rock Jon Savage Anarchy In The UK: Robert Sandall examines an insider’s history of Britain’s unique contribution to pop culture – the punk movement Before 1976. Britain’s contribution to pop culture was mainly musical. The Beatles, the Stones, Led Zeppelin and all the rest, had supplied a famous soundtrack, but the movie always seemed to be showing somewhere else, usually in America. Sure, the peace message had been obediently adopted and two-fingered back and forth at concerts, but none of our young men faced conscription to Vietnam. Our demos were tame affairs compared to the ones which paralysed France and provoked a shoot-to-kill policy that left four dead in Ohio. The development of the 1960s drug, LSD, happened in America: it appeared, from here, to have addled the whole of California. Even the uniforms of youth culture - from blue jeans to Indian smocks - were all imported. Punk, by contrast, came with Made In Britain scrawled all over it. The orthodox view - widely aired at the time and loudly echoed, 15 years later, in Jon Savage’s bulky new book, England’s Dreaming: Sex Pistols and Punk Rock (Faber £17.50) - holds punk to have been a noisy revolt against “the slow death by suffocation that is…the emotional experience of living in England”. Savage, a Cambridge law graduate who went on to edit one of the fjrst punk fanzines supplies several old diary entries of his own to illustrate the mood which, he believes, launched a movement. “F*** London for its dullness, the English people for their pusillanimity and the weather for its coldness and darkness,” he wrote in 1975. Now that the smoke has cleared, punk looks much more like a rather brilliant product of the prevailing culture than a commando strike against it. It was nurtured by an awkward and quarrelsome bunch of individualists who redesigned the rebel posturing of the, by then, decaying 1960s counter-culture in ways which were unmistakably, and sometimes reprehensibly, English. Class rhetoric and cockney accents, an aura of hooliganism, an intense interest in dressing up, which also reflected (in the form of leather bondage gear, pierced noses, nipples etc) a complicated and repressed approach to sex and one’s own body, an insular hostility towards most things foreign, a readiness to dismiss anything and anybody as boring, a liking for strong, simple tunes: these were a few of the items that distinguished punk’s homegrown, hybrid vigour from the flabby, hand-me-down hippie agenda that preceded it. England’s Dreaming stares right through most of these attention grabbing ploys.This book also combines a train-spotter’s eye for rock trivia with an appetite for ideological pigeon-holing which is initially impressive, but ultimately wearing. Themes include punk and the break down of the postwar political consensus; punk and the erosion of meaning. By the time Savage has finished quoting Steiner, Bakunin graphics Rimbaud and all the others, punk sounds more like a European avantgarde manifesto than a series of loud raspberries by the children and younger siblings of British Woodstock bores . Which is not to say that it didn’t have its arty side. Top of the list of punk’s innovations, in fact, was the art-school attitude. In no other country have art schools functioned as clearing houses for aspirant rockers - the way they do here. The punks, figured that an eye for design and style mattered at least as much as, and maybe more, than an ear for music. It is significant, and not surprising either, that the original, cut-up and collage punk graphics have weathered better and are more prominent today than scratchy old punk records. Before 1976, a lack of musical expertise, while no bar to pop stardom, was at least an obstacle to be overcome; suddenly it became sexy, a badge of naivety whose ostensible worthlessness could be brandished - and marketed - rather like a Warhol soup can. (Sid Vicious, as Savage points out, allowed himself to become a living symbol of dehumanised vacuity.) But if this keenness to celebrate the shallow and trashy seemed to link punk to American pop art, its execution owed much more to a very English spirit of radical amateurism. Never having been near an instrument before in your life proved to be a definite advantage in securing a post in one of the new groups. As a result, none of the most famous English punk bands -The Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Buzzcocks, The Slits, X-ray Spex - could match the technical proficiency or frenetic pace of the American band they all claimed as a key influence, The Ramones. Iggy Pop, another transatlantic punk idol, was a far more charismatic performer than any of his young British acolytes. Malcolm MLaren (fine arts graduate and master planner of the most celebrated punk rock band of them all) recruited The Sex Pistols’ vocalist, John “Rotten” Lydon, precisely because he couldn’t sing or move gracefully. That, McLaren claimed, “was the best selling point”. Although Savage puffs McLaren’s self-advertised skills as a hustler, punk rock failed to sell in really large quantities. Influential it may have been, but it was never that popular at the time. There were plenty of spiky hit singles, but by the standards of the big blockbuster albums of the 1970s and l980s, punk’s finest half hour -Never Mind the Bollocks Here’s the Sex Pistols -rates as a commercial disappointment. In general, the groups who did best out of punk were the ones, such as The Cash, Siouxsie and The Banshees and The Stranglers, who diligently practised their instruments and found their way back into mainstream rock. British record companies, panicked into throwing money at hundreds of shambolic, curiously titled new groups, lost nearly all of it. For most people, punk registered not as a musical revolution nor even as the death knell of the flared trouser, but as a hugely engrossing media event. From The Sex Pistols’ famous f-words with Bill Grundy on the Six O’Clock News rather unedifyingly transcribed here in full - to the acres of socio-cultural speculation about “dole-queue rock” that filled the intellectual weeklies, all tastes were catered for. And although the squalid deaths of Sid Vicious and his girlfriend Nancy Spungen provided it with a gruesome and pathetic finale, punk rock was wonderfully, provocatively witty. The American counter-culture of the 1960s was, at bottom, a pretty serious business. Punk, although it toyed with ideas of cultural disintegration, was, in its typically English way, suffused with irony and a cruel, larky humour. This, the most engaging aspect of his subject, is the only one with which Savage’s exhaustive account seems ill at ease. The facts are all meticulously logged. From McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s early days running a fetishistic clothes shop in the King’s Road, right through to punk spin-offs such as Rock Against Racism, the characters and the -isms have been rounded up with pedagogic thoroughness. But the spirit has somehow gone missing. Although he applauds punk’s “gleeful negation”, Savage never quite recognises it. Confronted with a fictional list of Sex Pistols’ merchandise (Gob Ale, Sid Vicious Action Men, Anar-kee-Ora and Rotten Bars), the author sternly notes: “This is a comment on the taming of the Sex Pistols’ innocence by the product-orientated music industry.” Unfortunately, such drab, right-on moralising ill suits the riotous and chaotic subject. Review,

Robert Sandall – The Sunday Times. 20th October 1991

THE WICKED WAYS OF MALCOLM MCLAREN Craig Bromberg (Omnibus £8.95) THE FILTH and the fury! The swaggering and swindling! It’s all here, but placed handsomely in context between art-school situationist sloganeer and international pop-culture mogul. Bromberg knows his onions, drawing on extensive first-hand interviews with hundreds of former friends and stars who escaped McLaren’s chaotic orbit. Inevitably,

the Sex Pistols period dominates a good third of this detailed text, examining

both sides of the highly dubious Swindle debate. Teddy Boy style guru Malcy unquestionably

contrived a New Wave in rock - using the New York Dolls as aborted prototypes

and disguising the Pistols’ ability to play live sabotaging well -produced

demo tapes - but his Svengali strings were quickly snapped by real-life urchins

like John Lydon. "Rotten didn't need coaching", chuckles the author. Bromberg may be overly cynical concerning McLaren’s talent for magpie creativity - after all, this guy brought us hip-hop and Afro-pop at the same time - and gives too little coverage to the man’s recent efforts, but this biography is a knowing and intelligent attempt to explore and demystify a crucial landmark on the contemporary popscape. Review – Stephen Dalton, NME. 7th September 1991

Review - Record Collector. 1990 Have you ever imagined bumping into Glen Matlock, erstwhile bassist and much-maligned straight-man of the most obnoxious pop group ever, and hearing him recount his story over a few beers? No need to dream. Here, with the help of an ex-”Sounds” scribe, is the full tale, couched in the same no-nonsense style that made Chaucer’s “The Miller’s Tale” such a lively schoolboy read. The importance of Glen’s book is that it represents ‘history from below’: many of his recollections sit uneasily when held up against the grand theories propogated by Malcolm McLaren and a generation of cultural pundits. Was it premeditated subversion that nearly took the band to Mickie Most’s RAK label? Was McLaren so far removed from rock’n’roll to imagine that the Sensational Alex Harvey Band were men from the Inland Revenue? And was “clever-clogs” Johnny Rotten so gullible as to end up leafleting for the Scientologists? Despite his art college background, Glen Matlock prefers to see the Sex Pistols in more down-to-earth terms than a deliberate and subversive attempt to appropriate ‘Cash From Chaos’. He recalls his early enthusiasm for rock, all-night Man concerts, and the musical loves of his colleagues. “Pretty Vacant”, the anthem of the blank generation, was actually based on Abba’s “S.O.S.”. Glen also takes pains to stress that, contrary to the myth, the Pistols were actually a tight, rockin’ combo who could cover the likes of the Who, Monkees and Dave Berry with skilful alacrity. He contrasts this with subsequent ‘punk’ bands whose only interest was in finishing a song well within the three-minute barrier. Although he was the first band member to encounter ‘artistic cretin” Malcolm McLaren, the manner of his dismissal from the band has left a profound distaste in his mouth; second only to his iconoclastic disregard for Mr. Punk Rock himself, Johnny Rotten. So Glen’s chummy tale, entertaining though it undoubtedly is, still leaves us waiting patiently for Jon Savage’s long-promised biography of the band in the hope of a nonpartisan account of one of the most exciting phenomenas in rock music.

“I

Was A Teenage Sex Pistol” GLEN MATLOCK with PETE SILVERTON Review - Q magazine, Monty Smith. 1990 With its rudimentary post-modern graphics and a sell-consciously parodic title inviting comparisons with pulp fiction and trashy creature features, co-authors Matlock and Silverton are clearly resolute about not setting their sights too high. This is a horses mouth record-straightener about the history of punk in general and The Sex Pistols in particular, aimed at those who move their lips when they read. What few cultural reference points arise are crassly identified for any cretins who may be looking at the words. Thus it’s HG. Wells’s Mr Kipps and George Orwell’s 1984, not the other versions that might readily spring to mind. Odd, then, that the Fleet St sleazoids should come in for so much flak when Mattock’s prose is so defiantly tabloid throughout. it’s a simple story, told for simpletons. But it’s not uninteresting. As a schoolboy Saturday worker in Malcolm McLaren’s Let It Rock (later Sex) fashion shop, Matlock was privy to the whimsical pettiness of Kings Road clientele. It was an alien environment for young Glen, a respectable Kensal Green working-class lad. Once he’d met Paul Cook and Steve Jones, both regular customers, it was downhill all the way. Under the influence of Bernard Rhodes (rather than McLaren), the motley trio formed a group more by accident than design. The instruments came courtesy of Jones’s thieving, the clothes from McLaren (who later billed them for the privilege). The publicity came via Bill Grundy, a disgruntled middle-aged broadcaster who was pissed off at his producer’s insistence that he interview a bunch of yobs. Though hopelessly naive, Matlock at least seems to be honest in his endeavours and opinions. Almost everyone comes out different shades of shit. McLaren’s a surprisingly peripheral figure, a shabby opportunist “who wished he was the singer”, John Lydon is an intolerable whinger, full of “total lies and denial, totally conceited, arrogant and stroppy just for the sake of it. His mum I think, was quite pleased with us for taking him off her hands.” Cook and Jones are inseparable, ineffectual, inarticulate, “Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble.” All the other punk bands are strictly second-rate Ramones-clones, unaware that the Pistols were tight, focused and deliberate, not mindless speed-thrash merchants. His few kind words are reserved for the psycho-junkie who replaced him as bassist in the band. But as soon as Sid Vicious joined The Sex Pistols, they really were McLaren’s toyboys. In the end, he dismisses the Pistols as “a total failure, like premature ejaculation, over in a flash and deeply unsatisfying-” Glen Matlock is 32. PeteSilverton is old enough to know better. * *

For additional reviews see "Rattle Your Cage" !!

LIPSTICK TRACES A Secret History of theTwentieth

Century by Greil Marcus

There has never been a pop musical phenomenon more interesting to the sociologists and cultural theorists than punk rock. The Sex Pistols’ first single, Anarchy In The UK, had scarcely been out a month in November 1976 before that erratic guide to rock and roll, New Society magazine, was running excited articles on the emergence of a new working-class protest dole-queue rock.

The punk attitude - the sneering, the swearing on TV, the strident je m’ en foutisme - soon got hyped to the point where it was widely and quite wrongly accepted that punk bands in general and the Sex Pistols in particular didn’t really play music at all but just made a frantic, loud and anarchically coded racket. They were a plot, a symbol; they were anything that needed a pundit to explain them rather than a set of unprejudiced ears to hear the artful, aggressive and articulate three-minute songs they played. By the time the Sex Pistols recruited an undeniably incompetent bass player, Sid Vicious, in February 1977, their chances of being judged on their enormous musical achievement —they virtually re-invented the pop single — all but vanished. Over in Berkeley, California, a writer who had not witnessed the London punk boo-ha at first hand, the learned American rock sociologist Greil Marcus, began sharpening his quill. The rest is his history of anarchist art movements in the 20th century. “Punk was not a musical genre.” Marcus reveals 12 years later. He traces the Sex Pistols’ cultural pedigree back through the French situationists and léttrists, and through American serial killers to the Dada movement. He also embarks on a supplementary historical trawl which nets French revolutionaries, English millenarian Protestant sects, medieval heretics and the early Christian gnostic cult. Marcus has talked these characters up into an all-star, pan-global anarchist tendency with the aid of a fireproof argument premised on the ingenious assertion that his is “a history that remains secret to those who make it, especially to those who make it”. He buttresses this presumption with an occultist disdain for “tradition as arthmetic”, by which he means — and dismisses — the more verifiable sort of carry-overs historians usually address. Arithmetical points, such as the Sex Pistols’ manager and designer Malcolm McLaren’s interest in the socially disruptive ploys associated with the French situationists, are duly played down. Mind-bogglingly fanciful connections are offered up in their place. Johnny Rotten’s real name, John Lydon, links him (by “serendipity”, Marcus suggests) to John of Leyden, a crazed Dutch Anabaptist who briefly ruled Munster in 1534 and turned it into an anarchist bun-fight: abolishing private property and marriage, staging black masses in the cathedral and running naked through the streets. Marcus makes much of the blasphemous opening line of Anarchy In The UK — “I am an Antichrist” —. finding in it not only echoes of the thoughts of situationist. Guy Debord but also memories of the mad German Dadaist Johannes Baader who in 1918 announced from the altar of Berlin Cathedral that Christ was, among other things, a sausage. The arithmetical fact that the Sex Pistols’ lyrics never referred so directly to religion again does not discourage Marcus. In them he discerns the latest glimmerings of “notions that have gone underground into a cultural unconscious” because “unfulfilled desires transmit themselves across the years in unfathomable ways”. Perhaps they do. But the suspicion grows as this secret history unwinds in its jumpy, ahistorical fashion that Marcus rather enjoys the unfathomable nature of his subject for its own sake. His academic desire to elucidate and cross-reference is all but cancelled out by his enthusiasm for sounding as teasingly cryptic as an anarchist slogan. “If all of this seems like a lot for a pop song to contain,” Marcus concludes, “that is why this is a story, if it is.” Throughout, he flaunts his love for arcane French intellectualese, alluding whenever he can to the “derive” and “détournement” - rare subversive species of ironic quotation which he seems keen should not be more widely understood. But most revealing of the author’s esoteric motivations are the Acknowledgements at the end of the book. “A few people did not simply help, give advice, read drafts, or come up with documents, though they did all of that; in the words of one of them, they were co-conspirators, They can’t be thanked, only recognised.” They are, in short, a secret society; a mystical cabal of armchair revolutionists. Lipstick Traces does not ultimately seek to explain a tradition so much as it hankers romantically to be a part of one. Review, Robert Sandall – The Sunday Times. 25th June 1989 God Save The Sex Pistols ©2002 - 2007 Phil Singleton / www.sex-pistols.net. All rights reserved. | |

SATELLITE Paul

Burgess and Alan Parker

SATELLITE Paul

Burgess and Alan Parker VACANT:

A Diary of The Punk Years

Nils Stevenson & Ray Stevenson

VACANT:

A Diary of The Punk Years

Nils Stevenson & Ray Stevenson 'Johnny

Be Bad'

'Johnny

Be Bad'  12

DAYS ON THE ROAD THE SEX PISTOLS' USA TOUR by

Noel E Monk and Jimmy Guterman

12

DAYS ON THE ROAD THE SEX PISTOLS' USA TOUR by

Noel E Monk and Jimmy Guterman 'The

Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle'

'The

Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle' 'The

Malcontent'

'The

Malcontent' “I

Was A Teenage Sex Pistol” GLEN MATLOCK with PETE SILVERTON

“I

Was A Teenage Sex Pistol” GLEN MATLOCK with PETE SILVERTON 'The

man who said Christ was a sausage'

'The

man who said Christ was a sausage'