| Search God Save The Sex Pistols with freefind |

| MIKE THORNE Exclusive Interview

The release this year of the box set 'Sex Pistols' has made, demos produced by Mike in December '76, available officially for the first time. Mike

offers a fresh, honest and unique insider's perspective on a fascinating period

in rock history.

Phil: What was your music industry background prior to becoming involved with the Sex Pistols? Mike: I had been six months on EMI's payroll - that was my mainstream biz total experience. But I had studied piano and flute, and also composition part-time at the Guildhall. Got fired from my first recording studio job in 1971 under slightly lively circumstances. Wound up writing about pop and contemporary classical music for the Guardian among others, and edited Studio Sound, which became the world's leading professional studio magazine on my watch. Then off to EMI. At my first record company, I didn't know how to behave. I tried the time-honored method of hanging out at the Speakeasy and talking to publishers, exchanging gossip, but the schmooze didn't suit (still doesn't). When the punk scene grew, I didn't know any better than to jump in. It looked like real action. However, having studied music and worked on sessions with Fleetwood Mac, Deep Purple and others had given me a useful piece-meal practical education by the time I encountered the Pistols. You were to become instrumental in the Pistols signing to EMI. When did you first become aware of the band? I picked up the phone when Malcolm called, then saw them at the 100 Club in Oxford Street. Couldn't persuade anyone else from EMI to walk over from the Marquee where their signing Giggles had just played. They weren't hot property then, despite having featured on the cover of Melody Maker (I hadn't noticed since I never read the comics nor listened to the radio, and was just pursuing my naïve musical nose as ever). To many, it was probably just another of Mike's crazy projects, and since the punk movement was quite esoteric at that time they weren't unjustified. That said, after three months the company's swing in support of the group was enormous. Can't remember the first real meeting with the group, but it was probably after they joined EMI and I was their designated A&R man. In my tiny office (I had a nice corner one by the time of the Roxy album, although more thanks to a quick move and a nod from the departing occupant than to status). Everything moved fast, thanks to Malcolm's shrewd management and then the drunken Bill Grundy. I enjoyed being around the group. They weren't hard to deal with, although John took a while before relaxing his professionally cynical stance. Since we were all interested in simply furthering the musical action, there was a common goal and we settled into it. The comment in the new CD release notes that I did so well to get so much music out of them on a demo Saturday afternoon is flattering. But I found them to be very applied and hardworking if they felt with the program. Might be awful for credibility, but there you go. I never really figured out what happened at A&M (I was buried in the studio by then, producing five albums in 1977), but apart from occasional edginess there was never any functional madness at EMI. They would quite happily hang out in the main open A&R area, along with other similar characters. That central A&R area became quite a pleasant drop-in social scene until the fall (of high management, some might say). I've only recently listened to the demos we did, for the first time in 15 years. They do sound good, but the most striking thing is the energy in the playing. Everyone was relaxed, and the three instrumentalists were loose and throwing in extras that probably wouldn't have been part of the 'playing the notes' rule in the big studio. John had a sore throat, and was as usual bickering with Glen, but despite this his vocals still have force and character. Am I correct in thinking the Pistols were your 1st production job? Following in the footsteps of Dave Goodman, Chris Spedding, & Chris Thomas, must have been intimidating, especially as Anarchy had already been released as a single. How did it all come about? The Pistols' was not a production job. All I did was go in and record a few demos for internal consumption and backing tracks in anticipation of future TV action. I was exhibiting production skills, sure, but producer was not my role and it wasn't my intention to usurp Chris Thomas (not that I ever could have). The Dave Goodman demos were energetic but their sound was, I thought, not very palatable to the record company crew, and I wanted to gather as much support for the music as I could. Bear in mind that this music was very different from that of other acts at EMI in 1976, and that punk would not become vaguely mainstream record biz fashionable until 1977. When Chris was dithering about whether to continue working with them (that was how I heard it from Nick Mobbs, my boss) I asked if I could be considered if Chris passed. He didn't, so asking was the closest I got. I wasn't intimidated by the prospect at all. But it would have been a challenge, which is all I ever ask from the next task I tackle, those in 2002 included. Along with the energy they produced in the studio, what did you find were the individual band members particular strengths in terms of group dynamics? It's difficult to comment on individuals within a working group. To work, a band needs social glue elements as well as the music, and individuals will fill them as appropriate. In the studio, often when you look back over a project with some good ideas, you can't actually remember who proposed what, just that some inspiration arose out of the encounter. The obvious comment is about John and Glen's differences, the subject of so much chatter and enduring for John with remarkable bitchiness in his memoir. But they were the two poles driving and defining the group, and it worked. They were the Sex Pistols' Mick and Keef, their Roger and Pete. Creative tension can yield a lot, although it can degenerate into shouts and fights. Mention of the recording of backing tracks for TV, which I take would be used for the band to perform along to, leads me onto the commitment of EMI to push the group. The recording session took place on 11th December in the wake of the Bill Grundy interview. Did the Grundy incident lead to a noticeable shift in support within EMI? If so, how did it manifest itself? There was a big shift in support on the shop floor within EMI, completely towards the group. This august institution hadn't had as much fun in years, and it was exciting even for the most reserved employees to be connected to something which was clearly noteworthy and making big waves. The senior management, however, took a different approach. They were part of the establishment which the group was baiting, and a connection with the Pistols would not help progress towards a mention in the Honours List. Nick Mobbs had a meeting with Sir John Read one evening, for which he dressed in a dark suit. The august Sir John apparently asked a few bland questions and then it was over. Clearly, the decision was pretty much made at that time a few days before Christmas. When the group was dropped, the workers were disgusted. What were we doing trying to find and develop bright new and novel acts when one of the most promising in years was kicked out by the bosses? Among others, both Nick and I considered resigning, but we realized that it would accomplish nothing: they were gone, and the regime would not change its attitude. So we came back with the live Roxy Club album just five months later with which the toffs might have had some problem if they ever listened. (I had to remove some curses because the quality control department at the pressing plant refused to handle it otherwise.) But post-Pistols punk was relatively inoffensive to the super-bosses because it wasn't targeting the establishment with which they identified. No OBEs were at stake. With apprehension within the company, did you feel you were on some personal mission to, as you said, make them more palatable to EMI? Did the demos you cut with them help gather more support within the company? There was no apprehension within the company, just skepticism. When I delivered one of several iterations of Anarchy to the weekly marketing meeting (where A&R would present its new recordings), there was shocked silence from most present. I said I would put my shirt on this one (not too attractive since it was an old, smelly blue T-shirt which I'd had on all through the previous late-night session at Wessex). The recordings were intended to make the songs more accessible than Dave Goodman's initial demo set, which captured energy but whose recording I thought fairly erratic. I didn't want the recording to come between the company and the songs and for it to be put off, so I recorded them in straightforward rock+roll fashion, the approach of the eventual album and which (of course) suited the music. I don't think the demos were circulated since I didn't mix them for a week after they were recorded (on the 18th), by which time the holidays were starting. In any case, we would only let a few select people listen to demos since (as now) many couldn't make the mental leap from a demo to a final recording and would treat everything as if finished and judge accordingly. Do you recall why particular songs were chosen for recording during your session? The songs with vocals were candidates for the second single, to follow Anarchy In The UK. The instrumentals were thrown down as potential backing tracks for TV performances, where only the vocal would be live. The group had done this performance mime already, but with the building anarchy a little mayhem might have been expected in the studio when they were asked again to go through this artificial and stifling TV production process.

God Save The Queen/No Future is of particular interest as the recording you made catches the song in its embryonic state. Were you already aware of the song? What are you memories of its recording and the groups approach to it? God Save The Queen was tangled up with and as No Future at the time of these recordings. Obviously, I already knew the song in this form, but it would be streamlined later to its punchy final version. Although John was feeling his way with the lyrics, I rather liked the 'God save Windolene' line and thought it appropriate ('Wipe in on/Wipe it off/That's how to get your windows clean' was the fatuous contemporary TV commercial). As with all the songs, there was so much to get down that there was no discussion about the music. This was how they played it then, and I wasn't interfering (I didn't think it was my place at the time, anyway). Since there was no external meddling, the energy in the session delivery was unusually high, translated straight from their recent club performances. Were you aware that four of your demos (No Feelings, No Future, Liar, & Problems), had been broadcast on Italian radio in 1977, & as a result eventually turned up on an unofficial CD The Italian Job? I hadn't given the tape a second thought after the Pistols were dropped by EMI. That year (1977) I produced five full albums and a few singles as well as fulfilling A&R duties for EMI, and was effectively buried in work. I can't resist buying any Pistols CD that shows up, and have a fair collection of Sexpistolploitation disks, but I never came across The Italian Job. Sounds like an Ealing comedy film, The Lavender Hill Mob Part 2. No Future also appeared on a bootleg CD, Aggression Through Repression. Did you have any idea that the demos had attained an almost mythical status amongst Pistols fans? When the group called it quits in 1978, I didn't pay any attention to the legacy. It had been a fun and stimulating time, and I was glad of the chance to grow and develop in those extraordinary social and musical times, but new exciting things lay elsewhere. The recording was nothing special, just all in a day's work. Engineers Ron and Dave at the studio in Manchester Square didn't like me doing my own engineering, since it compromised their overtime. But by engineering I could get very close to the people I was working with, in a relaxed situation with no-one else around. Later, such sessions would pay off when we were more easily able to speak the same musical language. And it helped to demonstrate that the guy at the record company knew where the on/off switch could be found on the big electrical recording machine. Fortunately, Ron and Dave never wanted to work Saturdays, so most of those afternoons I would work with some prospect or, as with the Pistols, put down demos to help clear ideas about the next master recordings. I always made sure to leave the studio spic and span so that Ron and Dave would have nothing to grumble about. Come Monday morning, you wouldn't have known anyone had been there, let alone the band with the most destructive reputation in the solar system. It might have been the same with a Wire or a Kate Bush, or anyone else with whom I was working in A&R. Thankfully, the release of the Sex Pistols Box Set (Virgin) this year has made the recordings available to the wider public and in pristine quality. In addition, three more backing tracks from the session are tucked away as 'hidden' extras (Anarchy, God Save the Queen and Pretty Vacant). No one knew about their existence. It was clearly a productive afternoon. Are there any more we don't know about? Hidden extras? I didn't know they were there. Should I be that ashamed of them? [Goes fishing around the CDs.] Oh, I get it, at the end of each CD without a separate index. Didn't think that rather easy-going version of Submission that ends disk two merited over eight minutes, and took the disk off. The backing track of Anarchy that follows maybe isn't the most musically conclusive way to finish disk one after the whole of the finished album tracks - its pace and energy sound a bit past sell-by date, although the sound is fierce and gritty. It was a long afternoon. The other two are pretty sparky, though, vigorous enough to be masters. When I first heard the 'new' backing tracks, I felt not only that the power of the tracks was amazing, but that they gave perhaps the most clear indication of what Bollocks might have sounded like with Glen Matlock still on bass. Exciting, tight, & importantly, inventive, something which was lost once he'd departed. Is this a viewpoint you share? Yes. Musically, I thought the group stopped developing when Glen left, and lost its musical coherence. Sid played better in the shock/horror department but to be effective you need more than that. With Sid on bass, the video looked great but the musical strength failed. The most plastic MTV pop video still has to start with a good tune. Glen did play on some of the Bollocks tracks, although I forget the background to his being asked back. I get embarrassed for John when reading his self-consciously strident comments about Glen's helping out in his book. Glen's book has a measured and extended commentary on the events leading up to his departure (he wasn't fired, that was just Malcolm's spin on Glen's resignation when John's pop star poses got a bit too much to stand). Musically, the band could have gone on to develop and keep innovating creatively, but that was a complete social non-starter. That breakup was coming was pretty clear in December 1976. Did you think the band itself would fall apart, or did you feel that Glen would be the one to leave? I didn't really give it a second thought since I was absolutely at full stretch dealing with the records I was producing, starting just after Christmas 1976. In early January, while working seven-day weeks and 14-hour days at the Manor studios, near Oxford, my boss Nick Mobbs phoned to say that they had been dropped. I gave myself a few minutes of being pissed off, then did the professional thing and went back to work. I was exhausted almost to the point of breakdown by the end of that month, at the ripe old age of 29. If they had still been my A&R responsibility at EMI, then obviously I would have been involved and concerned. But they'd gone. EMI did of course court Glen during this period, with a view to signing him independently of the Pistols, which is what happened with the Rich Kids. What was the inside view on this? The courtship, if that's the right word, was only when it was confirmed that Glen had left the Pistols. Since I had been the Pistols' point man at EMI, I was straight to work with Glen. The nucleus of the Rich Kids was Glen, Steve New and Rusty Egan, but Glen wanted a classic guitar band with two front men. He contacted Midge Ure at the time, as the rather teeny-rock band that he fronted (Slik) was disbanding. The new group was cemented by a spring expedition the two of us made to a Rezillos gig at a small town just outside Edinburgh. We connected with Midge there and he drove us to Glasgow, his home at the time. By the following morning, the band was in place and heading to EMI. I produced the first single with Midge taking lead vocals on one side, Glen on the other, which was then reproduced by Mick Ronson, whose pedigree was obviously significantly higher than mine. There was some debate within the company about which was the stronger version. I never played the two back to back, since I accepted the decision of the boss (for Ronson) and just went on the next project. It's interesting that you use the term 'a social non-starter' regarding their musical development. Did you feel the Pistols were already embalmed by their cultural position? I've worked with several initially raw bands, such as Soft Cell five years later in 1981, who found themselves suddenly and disconcertingly thrust into the limelight. It's very difficult for anyone in that position to handle the wild ride and to keep a level creative head. I've found it difficult enough in my own position, at times. You're surrounded by people who say how great everything is, everyone likes to hang out. You can easily lose perspective and you can start believing your own press. The Pistols were even more exceptional and pressure-prone since they (and the punk movement) were big daily news as well as hit recording artists. Sends the head spinning. Everything happened at high speed. Somewhere back then, the generating music got lost in a pile of self-reinforcing attitude. It's a version of complacency, and it stops you developing. You just go through the motions and can't escape to gain a sense of perspective. Embalmed is a good way of putting it, although they were worthy cultural icons, I thought. And even though the group came on as institutional bad boys, they got absorbed comfortably by the media as happens to all rebels. I dimly remember the public transition of the rough early Beatles into the loveable mop-tops. When the Pistols finally broke up, they seemed (from my distance) to be verging on caricature, a form of which you can see in many 'punk' groups now. Act tough, jump up and down a bit, turn up your lip. But you might as well smoke pot, and wander round amiably mumbling, 'Love and peace, man' for all it matters. What was the extent of your involvement with the Anarchy Tour? I had no practical involvement with the Anarchy Tour. I was just the guy from EMI. The company wanted a representative to be around to help and to observe as necessary, and as their A&R man I was only too happy to oblige. Perhaps my biggest contribution was suggesting to the General Manager, Paul Watts, that it would be an appreciated gesture if EMI treated the whole party to dinner at our hotel in Leeds (after several canceled dates). He thought it an excellent idea, even when the bill came in at over £300. It might have been even more expensive had the occasional flying roll hit one of the Leeds city councilors quietly dining across the room, near the ever-attentive press corps (who didn't get their dinner paid for by EMI). The shock-horror possibilities were contained by everyone's good mood, although some hack goofball had earlier talked Steve into knocking over a plant pot downstairs for the cameras. It was a good night, and a big relief from the stress of the non-tour so far. What are your abiding memories of the Tour? It was in Derby where the wheels really started to come off. I showed up at the gig, which was deserted except for Dave Cork, the distraught tour manager who was by then facing serious financial losses. The city councilors had proposed that the Sex Pistols play privately for them so that they could judge the act for themselves. That could have been one surreal and memorable scene, but the appropriate reaction was 'piss off'. I'm sure Malcolm was very polite. Next, I went to the hotel just outside Derby where everyone was staying. I think it was a Saturday. The group, Malcolm, Tom Nolan (EMI press) and I were jammed in one tiny room with the phone going every few minutes and the press literally banging on the door. Good money was offered for a story, but none changed hands as far as I know. One tabloid scribe had a Sunday double-page spread reserved for his story, and was getting really desperate. He probably made it all up when he couldn't get anything real. Most of them did. It was a shock to me to see how venal, dishonest and cynical many of these journalist characters were. You became very busy in 1977 with production work. Did you feel the Pistols had helped shape your own perceptions of the type of musicians you wanted to work with? The work with the Pistols was an integral part of lessons many of us were learning in the mid- to late-70s. In music, since the sixties and the raucous, revolutionary behavior, there had been an almost imperceptible move (but inexorable) to 'experts', people who could make a guitar rear up on its hind legs but, once the notes were spent, were saying nothing. With my classical music education and wholehearted subscription to sixties idealistic chaos, I was well-placed to deal with and see through the empty experts. But they still got up my nose. So the change in musical values to the importance of message rather than medium, embodied in the punk movement, was enormously sympathetic. The Pistols were figureheads, and that was their major contribution. I made my own qualifications, however, for myself and of the scene. As in the sixties, the baby often went out with the bathwater. Revolution is a messy business. As a producer, I brought sympathetic expertise to raw musicians who might have expected a raw deal from a previous regime. It got wearing justifying myself and trying to demonstrate that my interest in production was to facilitate the agenda of someone else's music which I admired. But I can't think of a quick test of an 'expert' which will show quickly and conclusively that expertise is sincerely at the service of the music and message, rather than being used to further social, political or career agendas. I'm afraid many producers don't see the long-term benefit of facilitating a novel and radical point of view. There's a parallel with the wonderful English politeness which is supposed to have come from the need to be socially considerate. As we well know, in some circumstances it can be used as a weapon. So beware of experts and polite people. But don't think they're all shits because just a few would aspire to be cynical and manipulative. Once I was established as a producer, my formula was very simple. I would work with music that I liked with people that I liked. By coincidence, I prefer tough, up-front music in any style, pop or classical or whatever. So there was the resonance.

Just about all of them. I just looked for music that didn't compromise and that posed a challenge to me to deliver on its own terms. Just about everything I've done reflects this. When it got dull, I quit. Even though being a successful producer is (ahem) glamorous and lucrative, after a while I found myself going round the same block and teaching the same lessons. Getting bored. It became time to find the trouble and disturbance that had I enjoyed in previous years, which I eventually would enjoy in the new technologies for a time (and was more than I bargained for). There was a crucial period for me towards the end of the eighties where I took on increasingly challenging projects as the record business was moving more towards the 'marketing specification' project, which would kill me with boredom. Eventually, no viable projects seemed to reflect this ideal. I decided to quit hired-gun production in 1993, finishing in June 1994 with delivery of a Marc Almond solo album which I thought was among the strongest work we had done, separately or together (as did Marc at the time). Then the whole lot was remixed/reworked in London and came out to my ears sounding like limp Brit synthipop and tired old cabaret, not the powerful guitar/techno concoction we had developed. There goes marketing and norms. Could have used a bit of bollocks back then. QED. Can you bring us up to-date with recent, current, & future projects? Retiring from hired-gun production didn't mean stopping recording, and certainly not from being active musically. I created an online presence during the .com optimism wave which continues as www.stereosociety.com. Out of this emerged fresh ideas for new and niche artists to be self-supporting with the newly-optional assistance of the new technologies and the powerful home computer. At this point, no fresh ideas can come from a new artist burdened with the marketing and promotion and distribution concepts/precepts of the successful generation before. We need to rethink. The business confuses support with money, since in the integrated system of ten years ago more money would imply stronger support. No longer. More intelligent use of resources is needed, with an acknowledgement that we must work on time-scales longer than next quarter's financial results. I wrote an 18-page white paper on the issues involved, which I believe to be crucial both to our evolving culture and a self-sufficient music business. It's in private circulation at this point, but I'm almost ready to publish it on the site. As

for music, I haven't stopped. Between now and next March I expect to deliver five

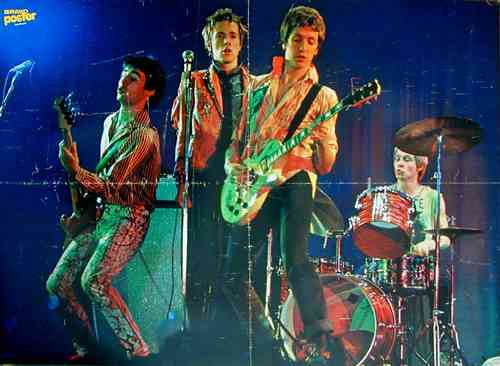

diverse new projects: That's enough. I'm exhausted. It flattens you even more to think also of all that energy 26 years ago, breaking out and breaking the rules. What makes punk, something that was supposed to be iconoclastic, survive to become worshiped in its own right? Beats me. Reflecting on your career so far, which achievement are you the most proud of? I can't distinguish. About my recordings, people ask which is my favorite, and I can't answer. I've had a really good run, and it hasn't stopped yet. I can only point to my full body of work, as this integrated blob which is me, as a cumulative contribution to various team efforts. I've learned a lot along the way. And had some really good laughs. Text by Phil Singleton/Mike Thorne. Photographs & Sex Pistols 'Bravo' poster © Mike Thorne: http://www.stereosociety.com/sexpistols.html http://www.stereosociety.com/thorne.html Sex

Pistols (Virgin - SEXBOX1) contains Mike's demos from 11th December 1976: ©2002

Phil Singleton / www.sex-pistols.net

|

Mike

Thorne's standing within the Sex Pistols' saga cannot be understated. Mike

was the first EMI employee to seek out the Sex Pistols. It was on Mike's recommendation

that A&R man Nick Mobbs would eventually secure the band's signature to EMI.

Mike became the group's A&R man for their turbulent stay on the label.

Mike

Thorne's standing within the Sex Pistols' saga cannot be understated. Mike

was the first EMI employee to seek out the Sex Pistols. It was on Mike's recommendation

that A&R man Nick Mobbs would eventually secure the band's signature to EMI.

Mike became the group's A&R man for their turbulent stay on the label.

Which

projects most reflected this?

Which

projects most reflected this?