|

Exclusive God Save The Sex Pistols Interview

January 2010

Questions posed by Phil Singleton

Pete Silverton's career in journalism took off in tandem with the rise of punk rock. He quickly became a top scribe for Sounds during the heyday of punk and witnessed the unfolding events first hand.

In this interview Pete talks about meeting an awkward youth who later became Sid Vicious, witnessing the Pistols with Joe Strummer - a night that would change Joe's life, the Anarchy Tour, Glen Matlock's autobiography, and the impact punk had on him as both a journalist and as a person.

We also learn about Pete's varied post Sounds career and his new book; Filthy English: The How, Why, When and What of Everyday Swearing. |

Phil: Pete, what was the inspiration behind your new book, Filthy English? Clearly, the Sex Pistols had a part to play in your thinking.

The inspiration didn't originally come from the Pistols. It came from two things. One, a headline in Salut les Copains, the French teenage magazine which inspired The Face. It was 'Tous les mecs sont les cons'. Which translates as: all blokes are cunts. On the front cover of a magazine for young French girls. Only it doesn't mean that, really. It means: all blokes are fools. Still, I was struck by the odd relationship between us, our swear words and the bits of our body that they often represent. And that was where my thoughts about swearing and its peculiarness started coming together.

Then I remembered that the first time I'd said fuck - as a very small child - it upset my parents so much they moved house, from Stoke Newington to Hemel Hempstead. So that became the starting point for the personal narrative in the book.

It was only when I came to start writing, really, that I realised I had to put the Grundy story right up front in the book, as the starting point for the major late 20th century change in British attitudes to swearing. I also thought it was important to clarify it and put that moment in context. To depict it accurately, too. Often writers don't bother to look at the transcript carefully and attribute the actual swearing wrongly. Rarely do people recall, either, the extent to which it only came about through Grundy's goading.

The Observer have described it as an 'enormously enjoyable book ... one is left with

amazement at the vast profane creativity at work in the unique human project of language' which is quite a compliment. What do you hope people will come away with after reading Filthy English?

Oh, I hope they come away with an understanding of just how important swearing is to what it means to be human - it's linked to very, very old parts of our brain, far more ancient than the bits I'm using right now to respond to you. I also hope they come away with; a whole new lexicon of swears from around the world; knowing why the Rolling Stones sung about little red roosters; the story of the very first record to have the word fuck in it (and the first cunt one, too); why swearing is, in the words of one of the reviews, both big and clever.

Your own journalistic career is inextricably linked with punk rock. Can you share some of your early memories of this period?

My early career as a journalist was linked to punk rock, yes, but there's been a whole lotta life since, from Smash Hits and TVam to a long time on Fleet Street.

When I left university in 1974, I wanted to write, to be a journalist and do exciting interesting stories. At that time - paradoxically, given the in-between state of the pop game - the music press was by far the most exciting writing going on in British and American journalism. I wanted in. But I had no idea how to get in. It was also the time of the first fanzines - I'd buy them from Nick at Compendium Books in Camden Town. One fanzine I was taken by was Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press - the name is an anglophiliac play on TOTP, Top of the Pops. I wrote a piece about Ducks Deluxe, I think, and sent it to them. Months later, Nick at Compendium told me he liked my piece on Ducks. I'd not put my address on it and my handwriting is so bad they got my name wrong (as Silvester, I think) but Nick guessed.

Having got my entry, I knew I had to write something more exciting and said to my friend Steve White: I want to write a piece about a new, exciting band. “What about Woody's?” he said. For a moment, I had no idea what he was talking about. Then I realised he was talking about Woody Mellor who we'd both spent a lot of time with before I went to university and who I'd known since I was sixteen or so. He was at school with Pablo LaBritain/Paul Buck, a friend who later became the drummer in 999. For some reason, Steve White had seen Woody since he'd reinvented himself as a band leader but I hadn't. Woody's band, of course, was the 101ers, only Woody was now Joe Strummer.

I still vividly remember the first night I saw them. It was at the Hope and Anchor on Upper Street. Joe was wearing the pink zoot suit he took to in the latter days of the 101ers. It was one of the few times

in my life that I've ever realised in the moment that I was seeing a star. Which is a really, really odd thing to happen when it's an old friend you're looking at. The magic borders on transubstantiation.

So I spent ages hanging out with them and wrote a piece. Joe and I spent a lot of the early summer of 1976 hanging out. I remember going to see the Stones at Earls Court where we had terrible tickets but Joe scammed us down to the front - then taunted Billy Wyman (pleasantly)...

You first saw the Pistols at the Nashville Rooms with Joe Strummer.

I remember - who could forget - Joe standing next to me as we watched the Pistols at the Nashville.

Wasn't that the show that convinced Strummer to leave the 101ers?

I think it was that night he told me he was giving up on the 101ers to start a new band, directly inspired by the Pistols. Which, as I'd just finished the piece, maybe even mailed it, was something of a disappointment to me - as well as exciting.

What impact did the Pistols have on you at this show?

What did I think of the Pistols that first time? Well, it both was and wasn't love at first sight. They were such an aesthetic rupture for me that I couldn't quite place it. Like many, I suspect, I really knew nothing about such precursors as Iggy - though I'd been a Velvets fan since the first album. Music was then, of course, far less easily accessible. So, although I'd read about the New York Dolls, I didn't know anyone who had their records (including Joe), so I'd never heard them.

John was clearly a star - even then that was a completely unoriginal claim. But I was uncomfortable about the violence and the violent atmosphere that surrounded the evening. What I couldn't - and still can't always - figure out was the status of the violence. Was it symbolic and representational? Or was it 'real'? Did it belong in the tradition of, say, modern art (and contemporaries such as JG Ballard and Stuart Brisley) or was it less self-conscious than that, emerging out of and echoing contemporary football terrace cultures? As a 24-year-old politically self-conscious psychology graduate you think about those kind of things.

How close did you come to the Pistols during this period and how did your relationship with them develop?

It was either that night at the Nashville or a bit later at the Acklam Hall that Joe introduced me to Glen - who has been a good friend ever since. We'd see each other fairly regularly because it was such a small scene that you'd always be bumping into people. Both Glen and I liked a drink. I had no relationship at all with John - he hung out with stoners which I always found the most boring and

arrogant of groupings. Steve and Paul I got to know later, in the period of the Pistols when they weren't doing anything.

The one I knew first, though, was Sid. Before he was Sid, before (I think) he had become friends with John Lydon, he was my cousin's best friend John - he lived round the corner from my cousin in Stoke Newington and, I think, my gran used to collect the rent from Sid's mum. Anyway, the first time I remember meeting Sid was at my 21st birthday - to which he came, uninvited, with my cousin. He wasn't the most socially easy of teenagers.

You say Sid wasn't the most socially easy of teenagers. Was this so apparent when he showed up?

Yes, it was. Not that he was exceptionally awkward, just at the awkward end of the spectrum.

What impression did he leave on you and how did he behave?

Sullen, withdrawn, that kind of thing. Not easy talking in a large group of people. I should explain that my 21st was at my parents' pub in Wadhurst, a small town in East Sussex, just south of Tunbridge

Wells - which is over the border in Kent and where his mother lived for a while. I think he had family in Wadhurst but maybe it was because he was near Tunbridge Wells. Sid (John) came down in the car with my cousin and uncle for the party.

How soon do you feel he started to view himself as a name on the punk scene and begin acting up to his image?

Immediately. I didn't recognise him at all later - not until my cousin Paul told me it was the same person.

How did you come to be on the Anarchy Tour?

I was there for Sounds. It was my first big piece for the magazine. I'd done a few reviews. I'd been given an introduction to the magazine by Joe Strummer. I was at a show with Joe - the Roundhouse, I think - and he told Sounds star writer Giovanni Dadomo: "Give this man a job". And, more or less, they did. Which was . . . quite wonderful.

After a few smallish pieces, I was asked - by the reviews editor, Geoff Barton, I think - to go up to Manchester (courtesy of EMI and with a press officer whose name escapes me but who was not at all keen on punk) to write about the Anarchy show there. I guess they knew that I was friends with Joe and Glen and would get the inside track. Which was ... true for Glen but not for Joe who at that time was embarrassed by his past and tried to have me thrown off the coach. Glen pulled rank, told Joe that the Pistols were the headline act and that I could stay. I remember no more of the show than I wrote at the time. You can read the piece on rocksbackpages.com.

What was the atmosphere like between the bands & did this change as the tour progressed?

What was the atmosphere like between the bands & did this change as the tour progressed?

I only spent that night with them - though I would have seen them when they came back to London, both during the tour and when it was over. So my thoughts are more surmise and interpreting echoes than direct observation. I do, though, think the other bands began to envy the Pistols - which is not a bad thing but a good thing. It's what gave them their drive - both to become successful (in their own terms and in the wider world) and to realise/embrace the fact that doing that involved becoming themselves. As the Pistols realised that they were special, so The Clash (in particular) realised how they had to become their own special. They'd known it before, of course, but now they really knew it and, if they forgot for a moment, their various managers and helpmeets would remind them.

How did the post-Grundy controversy affect the Pistols themselves during the tour?

Although I saw little of them on tour, the obvious changes were the obvious ones. They turned in, both on themselves and away from each other. The whole thing was such a florid moral panic that it is quite hard even to evoke a feeling of what it was like at the time. Not to exaggerate but the late 1970s was a time when things felt apocalyptic. The miners' strikes, the IRA bombs, the repeated elections, the rising unemployment (and inflation), the recent memory of the Vietnam War (and the protests against it), the rise (or at least the apparent rise) of the National Front etc etc.

I'm not for one moment suggesting that those were motors or motivators or punk - its manifest political content has always seemed overstated to me. Nor am I saying it was a genuinely apocalyptic world, either - we're still around, for a start. Rather, simply that it was a time and a place when threat and danger and shrill responses to them had a daily immediacy. What might seem extra-ordinary now had an ordinariness to it then. These wider political movements - and the rhetorical manner in which they were talked about - were a backdrop against which the anti-Pistols ranting played out. It just seemed fairly normal - if completely stupid - that a lorry driver kicked his TV in and Welsh evangelicals marched against a pop group.

As part of the gathering-in, though, the Pistols began to assert themselves - both to themselves and in relation to the other groups. They'd always seen themselves as apart - okay, above - everyone else

and this public fuss confirmed it. No-one was marching and placarding against the Damned. Essentially, although the non-tour was very frustrating to the band, it was the period in which they became genuine stars - not just in others' eyes but in their own, too. They came to realise, for better and for worse, that they were special. Things wouldn't be normal, they wouldn't be normal for a long time - if ever again. That's quite a burden for a young person. So it's no wonder that when heroin came knocking; some opened the door to their heart and let it walk right in.

Did the experience have an impact on yourself, both as a journalist or as a person?

Oh, it made my career. The first giant step was being published in TOTP - with the very first piece I ever wrote, he adds boastfully. The second was Joe introducing me to Giovanni (who is now dead these few years, helped there by his taste for opiates and alcohol). The third was writing the Anarchy piece. It was a big step up in the ranking from someone who contributed small reviews - I remember doing the first Generation X show, I think. Now I was ... a player. Not just a writer but someone whose opinion would be sought by the paper's editors. Soon, I was writing regular features and being invited into editorial conferences - oh, and earning good money. Then I was given a full-time writing job. Then I was made features editor. It was great.

My ambition - and the beginnings of the fulfillment of it - mirrored that of the Pistols during this period. Punk opened the door for a whole range of people - careerists, if you like to sneer. Rather, I'd think of it as a healthily human drive to make something of yourself and life - which involves money, acclaim, an expression of self, the love of others etc etc. While some music press journalists wanted to be music press journalists, I wanted to be a writer - and this was the coolest writing game in town at the time. Then things changed and it wasn't - but that's another story. I'd moved on to a wider world by then.

Personally? That's an interesting question which I've only ever considered privately before this. Well, the relationship I was in broke down. It was for the best that it broke down but that it did was partly a result of the stress of my spending so much time out late in clubs. I was young. I came home drunk. I took drugs. I didn't become a junkie. Strangers told me they liked my writing - I remember a bank

teller recognising my name and starting a conversation about something I'd written. I became somewhat obnoxious, I should imagine. It's hard not to, particularly as so much of the whole punk gestalt was obnoxiousness - and I was, like many of those around me, far from a happy bunny.

How did your association with punk develop during the turbulent year of 1977?

As a writer on Sounds, it pretty much became my life - to my great pleasure and enjoyment. I got paid (well) to hang out, go to gigs, get free records, take drugs, stay up late, attract attractive girls,

travel the world (at other people's expense), get backwashes of spit and, importantly, write every day.

If that sounds selfish and self-centred, I also think most histories of punk have understated the basic human desires - the ones that, I think, Jelly Roll Morton categorised as the drive for 'loose shoes,

tight pussy and a warm place to shit'. Personally, too, I'm more inclined to trust those desires than a wish, say, to ensure full employment for all 18-30 year olds, as in, most obviously, Gene

October's Right To Work single.

That is, though, not to say that I would have given you that kind of answer at the time. I would have talked far more in general, social terms - though even then I always thought punk - particularly its first

wave - was essentially the art school dance that went on forever. Not, of course, that the art school dance is without profound and wonderful social and socio-psychological content, meanings and complications.

How did your career develop over the following years?

I became increasingly dispirited on Sounds - partly my own fault and dynamic, partly a reaction to changes in music, and my attitude to it. I just wasn't interested in some of the stuff we were covering - heavy metal and oi, obviously. It all seemed a bit crude and unformed.

Also, I became disenchanted by the fact that the people whose music I liked were not necessarily the ones I liked to write about. So I left and started freelancing. I did a lot for Smash Hits - I liked the open honesty that this was POP music but was never fully happy with its propensity for sneering. I was a consultant for TVam children's programming - where we pioneered the use of computer screen effects in broadcast TV. And I moved into Fleet St, spending most of the 1980s as a regular writer for YOU magazine.

I helped set up 20/20 magazine for Time Out. I helped Punch become the first digitally produced mainstream publication in the UK. I helped The Guardian re-invent itself for the 1990s - I was hired by the marketing department and was involved in developing things like The Guide and Guardian Weekend. I returned to the Mail on Sunday and helped set up Night & Day - which was a really great magazine, even if it is me saying it. Since then, I've worked on and for various national publications - in particular The Observer. Currently, as well as writing books, I do a monthly column for Professional Photographer magazine about legendary photographers.

What lead to you working with Glen on his autobiography?

Having become friends in the early punk days, we spent a lot of time together during the Rich Kids years then stayed in touch. He approached me to write it with him and it was a surprisingly - I say

that because it is often a conflictual experience - easy and fun job, though it, of course, took longer than I would have thought. I was proud of it. And, for the second edition, there was a section of my own memories of the punk years.

Finally Pete, which piece of your own journalism are you most proud of?

Oh, when I re-read the stuff I wrote for Sounds, I'm sometimes surprised by how little my writing has changed. There's a piece about Madness on the cusp of their subteen stardom which I looked at

recently for some reason and I was impressed with how right I got it.

Oh, when I re-read the stuff I wrote for Sounds, I'm sometimes surprised by how little my writing has changed. There's a piece about Madness on the cusp of their subteen stardom which I looked at

recently for some reason and I was impressed with how right I got it.

For YOU magazine, I did a piece about a dwarf-throwing contest in Croydon - which couldn't help but stick in your brain. For 20/20 there was a piece about Bowie and the late 1980s downtown scene in New York. For The Guardian, a life and times of the racing driver James Hunt. For Night & Day, 6,000 word pieces on white paint (yes, white paint) and bananas (yes, bananas). For The Observer, an even bigger piece on cancer and a history of the song YMCA. For Mojo, a long, long shaggy dog of an answer to the question: who put the bomp?

Many thanks Pete for taking time out to answer some questions for me and good luck with Filthy English.

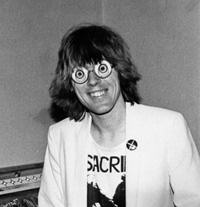

Visits Pete's blog: petersilverton.blogspot.com (pictured right: Pete as a photographer in the pit at 2009's London fashion week).