| Ed Tudor Pole's unforgettable appearance in The Great Rock 'N' Roll Swindle ensured he would forever occupy his own crazy corner in the Sex Pistols' legacy. I last had a chat with Ed back in 2005 where we discussed his involvement with the Sex Pistols film. With the publication of his entertaining autobiography The Pen Is Mightier, it seemed the perfect time to have a catch-up. Ed remains as much fun to interview as his book is to read.

Have you been busy recently, Ed?

Well, you know, with the book, promoting it and stuff. I've been doing these story gigs.

Having read your book, I would say that you are quite unconventional. Would you agree with that?

Well, the life's been unconventional, but I don't think I'm unconventional. No, I'm very traditional. Traditional values. You know, I love the country, I love the Queen. You know, I'm a good father, quite strict. I wouldn't say I'm unconventional. I wear normal clothes, got a nice tweed jacket on. That's pretty jolly civilised. So, in what way do you think I'm unconventional?

I mean you've followed your guts, really. You've gone into your music, then you went into acting which, having read your book, you never felt that comfortable with. A lot of people have a fairly linear career, whereas you've gone more off at tangents depending on how you felt at that particular time in your life.

Well, look, I don't think it was depending on how I felt. It was just the circumstances. I mean, I've just gone where fate has led me. It's not been a decision. I had no option but to go into acting after the band broke up. And so all these things happen, the logic is I haven't planned them. That's it. My career has been arranged by the great tour manager in the sky. I mean, whatever that is, but it's true. I don't feel in charge of my own life and never have done. It's been an interesting ride. But it's not always because of my decisions that I've done the things I've done.

Reading your book you focus a lot on individuals and their impact rather than the institutions like school and RADA. Some of the actual teachers, for example.

Well, I only mentioned the teachers because I definitely needed the guidance from someone older than I was. And I wasn't getting it at home. So I write about the teachers because they give me proper life lessons, which every child presumably gets, you know, at home. So yes, I always admired an individual. But I mean, they don't have to be individuals, I like a crowd as well.

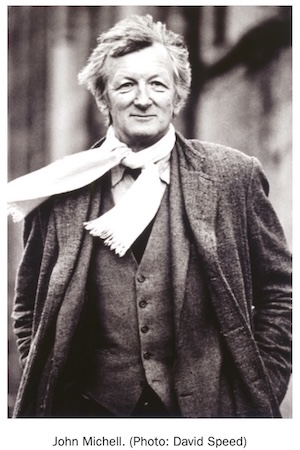

Another example would be John Michell, who you described as an ideal Englishman.

He was great. So kind. John Michell was extraordinary. I mean, a real knob, you know, a total aristocrat. I don't normally meet that type. But when you get that high up, you're sort of completely normal and nice. It's weird. And he was like a father to me, I suppose.

And he taught you how to be happy.

Well, yes. He was such a clever bloke. And I mean, he proved that we live in an ordered universe. For me, he satisfied me that we do, rather than just random chaos, which some people think. But he proved it on the back of an envelope with a triangle and a circle and a square. I got it immediately. And of course, knowing that we're in an ordered universe makes me happy, well it should make you happy. So yeah, he was a terrific influence. And he wrote these books, which I'm not anywhere near clever enough to understand, about how the world was created and sacred geometry. And then he had all these geometrical watercolours he did explaining why they fit into the patterns of life, you find them in flowers and things. You have to be a sort of genius to be able to understand the book. Not that I am at all, but he took me under his wing, you know. I felt very happy in his presence. So I just tagged along with him when he went out to all these grand dos and stuff.

Who did you get to meet at these grand dos? Were there any upper crust types that you took to as well as John?

Well, not so much upper crust but he knew some of the Rolling Stones. We went to Jerry Hall's one evening for supper. Just me and John Michell, and Bill Wyman was there and his wife, which I wasn't expecting, but I mean, I loved the Stones. So that was a lovely evening, but in a way, John Michell was far more impressive and flash to be with than Jerry Hall and Bill Wyman at Jerry's mansion.

That's quite something for a Rolling Stones fan, because you were a hardcore Rolling Stones fan.

It is quite something, it is. Now, I miss John so much. If you've got friends, make sure you see them enough, because let's say they die. You don't have to be saying to yourself, "I wish I'd spent more time with them."

Yeah, it's true. Frith Banbury was another one that you mentioned, which I thought was quite an interesting passage in your book. Could you tell us a little bit about him.

Well, he's a very ancient theatre director of the old school. And he was brought in because I was in this play with Rex Harrison and Edward Fox, but shortly into the rehearsals, Rex was throwing a wobbly because he didn't like the American director. It was set in Edwardian times, 1905 England, and they hated the American director's approach. So, Rex says, "I'm leaving, unless you change the director, either I go or that director goes." So they had to get a new director. Well, I liked the American director, because he didn't know who the hell I was, which is why he gave me the job, because he didn't know I was a punk rocker. There's no way I would have got into the Haymarket Theatre. So I loved him, and when I went to the audition, I just said, "You know, I'm a very hard-working man. I mean, I've done 45 one-night stands in 48 days." Which is true, you know, in the rock and roll world. I don't know what he thinks it is I'm doing. That's how I got the part. So anyway, he left, and then Frith Banbury came in, and he was a wonderful old character. He originally directed the first production of The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan, that famous English playwright, back in the '50s. I mean, it's always being revived. I was in the first revival, and it's now on again, I see. So Frith Banbury would say "You see, you're getting your laugh in that line, but actually there's three laughs to be had in the line, you see. If you say, 'da da da,' then you pause, and then you look over to the mantelpiece, then you'll get another laugh, and then..." you know, he's explaining how to get the laughs. It's clever stuff, which is obviously what I want to know about. Yeah, nice.

You were very good at describing the boredom and insecurity of an actor's life, such as always going back to square one after each job. How did you deal with that? How did you fill the time between acting jobs?

Oh, it's hell, man. What is an actor to do? Because for a start, you think, "Well, I'll never get a job again." And it's not an unreasonable doubt, because there's too many actors. It was horrible because I couldn't start a band and get that fired up, because let's say I did get a job somewhere I'd have to take it, because I mean, I was completely broke. I couldn't form a band, because it'd cost 30 pounds to hire a rehearsal room. I hadn't got 30 pounds. I mean, it's awful, awful, awful being an actor. It's the worst job in the world. And so, well, you just get out of your head as cheaply as possible, don't you?

I was just wondering if you had any particular hobbies that you maybe did.

Well, I do my running to keep fit. I've always kept that up, which I've done ever since the music days. And obviously, I played my guitar to keep my hand in, a couple of hours of scales or something, and then just get out of my head I suppose to fill the rest of the time. I always tried to do something worthwhile, like a run and guitar practice. But it's dismal days. That's why I speak so witheringly about acting, with zero respect for the profession.

I was surprised that you never really felt at home as an actor.

It's just that for that world you have to be a certain type of person that's quite different from a music type. And actors, they're quite tricky people. Kind of weird. They're not so great company because they're always trying to prove something or play mind games. Whereas a musician, I mean, he's just a nice chap, relaxed. Because he knows he's only got to pick up his banjo and he can blow you away. So he's got nothing to prove really. He's more secure in himself. The acting world, it's very sort of middle classy. And it knows nothing about the music world at all. It might as well be Trinidad and Tokyo as far as how much they know about each other. No one ever knew that I was Tenpole Tudor when I was in the play with Rex Harrison and everything. Because that type of person doesn't know anything about the music scene. Kind of really weird.

You say in your book if people knew that you'd been in a band they might not have actually employed you as an actor. I thought that was quite shocking.

Really? Well, that's England for you. They like to know who people are, them being in their box. They don't like someone who is versatile, it confuses them. So when The Crystal Maze came up I grabbed it with both arms because I knew it'd kill the acting, what little of it there was, stone dead. Because you know, who is this guy? What is he? I thought he was an actor, what is he? No, he's on the game show. Hang on, wasn't he in the band? I mean, wasn't he what? Who is he? Go away, go away. And that was kind of good, really. I loved doing The Crystal Maze. Even if nobody else did, I hated the production team, I loved my contestants, I looked after them. Everyone else was rude about them, but they were safe with me. Anyway, it was only two five weeks stints, one year, then the next year. That was fun, and then when that finished, there was nothing. I'd burnt all my bridges. The acting had stopped. They don't give big parts to game show hosts. Anyway, I don't want a damn big part, playing someone far less interesting than myself on television with a suit and a side parting.

I mean, would you ever go back to acting?

Am I not making myself clear, Phil?!! I can't believe that last question!

Yes, you are making yourself clear! I ask it because in your book, you said, "Well, Game of Thrones came along, so I did that one." I suppose I'm just wondering if someone came along with an offer you can't refuse...

Game of Thrones was one day, a dead easy part as a ranting street preacher. A little trip to Croatia, you know, why not? I hadn't done it for years, I could fit it in, but it was a good thing to do because it really reinforced my disliking of that whole world, as I hope I described clearly.

You do. You do. Very clearly.

In other words, give me Southend any day rather than some five-star luxury hotel in Croatia and the Mercedes Benz to take me to the film set where you hang around for hours being waited on hand and foot with the occasional break to say your lines and then you break for lunch, and then in the afternoon you're waited on hand and foot and then you say another line on set and then you go back in your luxury limousine to the five-star hotel and drink cocktails on the terrace to the lounge band. The lounge band with the white tablecloth and the swimming pool glittering in the evening light. Three days of that, I've had enough. Give me Southend, come on, with my guitar.

Give you good old England.

Exactly. I mean, as an actor, you're either out of work or you're a gigolo.

You speak passionately about your dislike of it!

Well nobody else does, do they? Why do people take it so seriously? Because if you think of it, it's an absurd, absurd occupation. "So what do you do?." "Oh, well, I do weeks and months of unemployment, sometimes years, just for the hope of getting the chance to pretend to be somebody else." Really? I mean, honestly, if that's not trivial, I don't know what it is.

I would say, reading your book, that one of the things you did enjoy to a certain extent was working on the film Walker in Nicaragua, because you were there with Joe Strummer and Alex Cox who you liked. Looking back, maybe that was one of the highlights?

I absolutely loved that. You know, don't get me wrong, it was never the actual work of the acting I particularly minded. I don't mind Christmas if it comes up, maybe now and then, it's fun. But, it's the in-between, so when I do get the job, it's fine, but it's just all the time in between when you're sort of doing nothing. But yeah, with Alex Cox in Nicaragua and Ed Harris, and there was a war on at the time, that was really fun for three months. Yeah, Joe had long hair and a beard, so he didn't look like Joe Strummer.

It was in Joe's wilderness time as well, he was overlooked a bit and it was nice to see him doing stuff.

Exactly, his wilderness time, my acting years were my wilderness days. It sounds good on a bit of paper, but the reality is, 100 days of hell for one day of heaven.

It's quite a trade-off, I'll give you that.

It is a trade-off, but one I'm not prepared to make.

That's right! Well let's go on to music, because I think you give some of your own songs a bit of a bad press, Real Fun for instance. Now, I loved that single when it came out, and I still do, but I know you mentioned Danny Baker said it was like an 11 year old's idea of copying Paul Cook and Steve Jones, which you agreed with. I think that's a bit of a disservice, do you have any love for that song at all?

Yeah, nothing wrong with the song, nothing wrong with his remarks. I could see how he thought it was an 11 year old's attempt to sound like the Sex Pistols, because I had the mental age of an 11 year old, so I thought he was spot on. Which is not to denigrate the song, and not to denigrate an 11 year old, a lot of 11 year olds are often at the very clever stage of their lives. In fact, if the 11 year old waits for one more year, he becomes 12, and it was every 12 year old boy in the land who made Swords Of A Thousand men a hit, nobody else bought it, just every 12 year old. 350,000 of them! That's a very weird thing, for only one tiny section to buy a record. So that's why it took everyone by surprise, they couldn't work it out. It's like a schoolyard craze, like the yo-yo or something.

I think its appeal spread a bit wider than just that demographic, you know, some of us older ones enjoyed it and bought it.

Well, all right. 10-15! How old are you, Phil?

I'm 61. I'm an old fart, aren't I?

Oh no, you're a nipper to me, man. Well, I'm 10 years older than you.

Yeah, so when that came out, I was probably 17.

Oh, okay, well, that's great. You would be one of the senior members of the Fan Club. Thanks very much for buying it, Phil.

Still talking about Real Fun. You did a more mellow version of that on your Made It This Far album, which has a completely different feel to it.

Yes. Completely different. As you say, it's such a good tune and I just thought of cooking it up another way. Yeah. It wasn't meant to be just another version. Did you like that version?

I do like that version, because it's not just a re-recording. It's a completely different interpretation of the song.

Well, yeah. But, you know, a good tune can be done many ways, can't it? Tunes can keep you fascinated for ages.

What's In A Word was on the flip side and I thought they made a great A and B pair.

I agree with you. What's In A Word, I'd like to use that. I think it's really good. The chords in it are very unusual and really work. I wrote that for the Sex Pistols. There was only a thousand copies of Real Fun printed, so no one's heard What's In A Word. I mean, it's very obscure.

Yeah, I've never seen it on a compilation. In fact, I've never seen Real Fun on anything either.

Well, that was because it was on a little independent label, one-off, called Korova Records. So that's why it is not on anything else. But What's In A Word... I know I try and play it sometimes, but it needs a band. You can't really play it on a guitar. Or maybe I could. Yeah, I might play that when I finish the interview. But actually, no, I can't because I've got to write a speech for the book launch!

But you can always revisit that one as an anecdote because of the Pistols connection for your book tour. Who knows?

Well, yes. Who knows? Thanks for reminding me of that one. Yes, it is a good one. "There are rules and there are problems."

It's a good song, not just a little ditty.

Yeah, thank you, man. I think I agree. It is a good one. I saw the Sex Pistols at the Albert Hall a couple of months ago. The Albert Hall was just fantastic. I was perched up high so I could see down onto the stage and the whole auditorium. And Frank Carter just drove them all nuts, walked, crowd-surfed and everything, all strictly forbidden. It was a joyous celebration. I wasn't expecting to like Frank Carter. Who the fuck is Frank Carter anyway? But you couldn't take it away from him. He did his job properly. He was a great frontman. He had a lot of energy being younger. And he just amplified the crowd's feeling anyway. Made them even happier. We didn't want snidey, snarky remarks. It wasn't that sort of occasion.

The punk rock thing has become a sort of big family now. And there's still people... Especially up north, people still keep the scene going. And all the protagonists are still going. You know, John Lydon, Adam Ant, Sex Pistols. They're still all out there. It's kind of fun. And for that generation, it means a lot to them. Do you think?

Definitely. It means a lot to me. And it's also nice that you don't have any of the more unsavoury stuff anymore. There's no gobbing and horrible stuff like that. There's no aggro.

Well, gobbing didn't last too long, thank goodness. We never had aggro at a Tenpole Tudor gig, never. People only turn to aggro when they're bored. They were just having fun. We were thugs night off, I reckon.

That's when you're not smashing front doors in Germany somewhere? That was quite a good anecdote. I'll let people read about that one.

Oh, gosh, gosh, yes. There's lots of good stories in there. And I tried to be entertaining and to make it a page turner. But it's not a dipper, it's got to be read from the beginning to the end. People who have seen it say they really like it and are sorry it ended up when it did, they wanted it to carry on. If you find any boring bits, let me know. We'll get it cut out of the paper back version.

No, it wasn't boring. And it wasn't back-slapping either. And you're quite self-effacing, quite modest in a way. I quite enjoyed that side of it. And of course, being a Pistols fan, I enjoyed those parts. I know I spoke to you 20 years ago and I asked you lots of questions about the Pistols stuff, so I covered all that back then. But I like the way you talk about your involvement because you're very honest about it.

Well, how else is there to be? I'm telling the story so that the reader can experience some of what I went through. So I'm not going to show off to them, because that's a sort of a barrier. I'm trying to invite them inside, it's an intimate thing.

It's also fascinating, because you obviously kept a bit of a diary.

I did in the rock days, yeah. I knew, I thought, "Hang on, this is great." I was so excited, I didn't know what was coming and we were going somewhere, so I had to write down a journal, you know, as you do. I stopped the journal when the band broke up.

It sheds a lot of light on the Pistols stuff, because you were still filming that scene at the cinema, January 79. And that was only a mere week or two before McLaren lost control of the band and the band's name, bringing it all to a halt. So that was right up to the wire.

Absolutely. Every day was different. Every day there was something happening. So much was happening in such a concertinaed space of time. You're right.

I was hanging out, I was rehearsing with Steve and Paul. I mean, the filming of Who Killed Bambi only took one day. But it was all going on, all around. I was hanging out, going to the office, you know, plans happening, seeing Steve. Coming to rehearsal. McLaren coming out and riffing on ideas.

Can you recall any of the songs you rehearsed with Steve and Paul?

They weren't Sex Pistols ones. I can't really, actually. No. Maybe Lonely Boy was one. Maybe Silly Thing. I can't really remember, funnily enough. It was only four rehearsals. I've had a few rehearsals in other bands since then. Ten million.

You had a good rapport with Steve and Paul. They came and played live with Tenpole Tudor a few times, didn't they?

Yeah, I loved Steve. He was so nice to me. The girl who took me to the Albert Hall - her four-time granddad happened to build it - I told her, me and Steve love each other. So I got to the backstage party room, there's never anyone in the band in there. And then Paul Cook's wife came in and grabbed me, said Steve wants to see you in the dressing room. So she dragged me out. I said, "I'll be back soon." Paul's wife let me in the dressing room, and it's lovely, lovely. Me and Steve are having a nice chat together, being ever so intimate. Then Paul Cook sat on the other side of me, briefly, and then we had some photos taken quickly. Eventually, I said goodbye to Steve, and went back to the girl in the party room. Then the next morning, on Steve Jones' Instagram, he put, "Oh, we met Tenpole, I love this guy. Love this guy." And a picture of me, him, and Paul. It was great, so I could say to the girl the next day. "So that's Steve, I told you we loved each other!" There's the bloody proof. That was one of the most happiest things of my life, that little incident.

I saw you supporting Paul's Professionals when they relaunched about 10 years ago at the 100 Club. Do you remember doing an encore with them? White Light White Heat.

I hadn't rehearsed it. I used to love that song. But no, I could have done with rehearsing it. You might have been able to tell!

Going back to Tenpole Tudor, you said you regretted issuing Wunderbar as a follow-up to Swords Of A Thousand Men. What would you have preferred to have had as your follow-up single?

Maybe Go Wilder. But David Robinson (Stiff Records) kept saying, "Yeah, you don't want to be a one-hit wonder. This Wunderbar song, this will do well." It sort of did do well, but to a completely different crowd. Everyone who liked Swords thought it was just a joke song. It's not in the same sort of ilk. It was written in a completely different time. And also, it was much more fun when it was called by its original title, Fall About, because everyone fell about, you know? Being called Wunderbar just gives it another sort of slant. It's not quite right. It's a good tune, though. That's a bit of a one-off thing, that Wunderbar. Anyway, I sang it at Stoke-on-Trent four weeks ago. I said, "I don't sing it, because unless enough people really sing it lustily, it's pathetic." They said, "Go on, we'll sing it lustily." And boy, did they. And I thought, "Ah, this is great. I should do this more often." So I played it at the next gig and, of course, they weren't singing it lustily. And that is really sad. When they're sort of whispering, "Wunderbar." I mean, come on.

Throwing My Baby Out With The Bathwater was one of your really good songs. It could have been a big hit if it had followed Swords. How do you feel about that one?

Yeah, everyone likes that one, and I like it. Pete Townsend liked it when I played it to him. But it wasn't written at the same time, so it couldn't have been the follow-up to Swords. That would have been great if it had. The thing is, when you have a hit they didn't give you a day off. So you haven't got a day off to write another song. It's a real problem. That's why everyone has a problem with the second album. You need a certain amount of introspection to write a song. Well, you need the afternoon off.

Moving on a bit now, you've not had an album out since Made It This Far which was a good while ago.

No, but I've probably got enough songs. With Made It This Far I just suddenly thought, with all the recordings I'd done in the past 25 years, I can choose the best of them and call it an album. Well, I can now do that again, because I'm always going to do recordings every now and then. When I think this song is too good to miss, I go and record it as best as I can. I never know what to do with it after that, but anyway, they build up, so perhaps we've got another album. I mean, I'm rather busy with the book at the moment. I hope it does well.

I'm sure it will. It's a very good book. It's well-presented, with a great cover.

I like the cover. It's a small independent publisher. He's a really nice chap. Presumably if it sells well, he can print more, I guess.

Made It This Far is a killer title track. Do you play that one at all these days?

No, but they did play it two days ago in Leytonstone before I came on to do a little chat as part of the book promotion. I was well pleased. I'm not sure about the song, but I like the sentiment of it. It's a bit of a mad song. That was done in Pete Townsend's studio.

Yippie Yi Yay, I think captures the essence of Tenpole Tudor.

I quite like it. I know what you mean. It does capture an essence. It's not bad at all.

So do you have any favourites on the Made It This Far album?

I love Mohican. That one is my favourite. Or maybe Football Yobbo. [Ed breaks into song!]

For the last 20 years you've been focused on just doing your music and playing live. So are you still getting the same thrill performing after all these years?

Well, you know, after all that horrible time being out of work, since 2004 I've had my head down under the radar, and every weekend I had a gig to go to. Mostly up north, Midlands, or south Wales, or the West Country, or Scotland. So it's just a weekly routine, a circle. So you're trying to be the best you possibly can at the gig, and then you're completely exhausted. Then you go home knackered, and then you kind of come around. Then you start panicking because there's a gig coming up. So then you rush down to the rehearsal studio. The gig focuses the mind. And then you're up on the train on Friday, up north, and maybe two nights, or one night. And it's that circle. It was that little weekly circle for 15 years. Head down. So it was a proper regular job, you know, no distractions. Becoming a pop star, that's a distraction, one I can well do without.

You mention in your book Uri Geller accused you of not wanting to be famous and you agreed with that, didn't you?

Well, I wondered if he could have put his finger on it. People think it must be great to be a pop star. It's a pain in the neck, actually, after a while. It's just annoying, because it sort of hangs around you like a millstone. You can't really get away from it. I think being a regular normal member of society is where it's at, don't you think?

I agree with you, and it's clear from the book, you think it's a civic duty to amuse people as you pass through life.

Did I say that? [laughing] I mean, to be agreeable, yeah. Mind you, most people are agreeable, especially in the Midlands and the North of England. It's a completely different country to the South, where I came from. They're miserable down South. That's a gross generalisation, of course.

The real England is found the further you get away from London.

It is, it is, and you can see the history of it. You know, I've been to every city and every market town and every town in the land, well, not every town, but hundreds of them.

So what's the average day like then, Ed, these days, for you?

I've been working on my speech for the book launch. But you know Stanley Unwin? He talked gibberish, it sounds like English, but it isn't.

Yeah, Unwinese, they used to call it, didn't they?

Unwinese. I've been practising Unwinese, which is really hard to learn. Then say, "I hope you can read my subtext, because my subtext is dying to get out, screaming to be understood, which is the only reason I wrote the book in order to be understood. Do I make myself clear?!" That would work if I can do the Unwinese convincingly enough. That's one idea for a speech anyway. That's what I'm doing today.

That's the individualistic side of you. Your uniqueness.

What is, what's the uniqueness?

Well, one of your uniquenesses is the way you project yourself, your vocal style. It's unlike anybody else, isn't it? It's very distinctive. I think the way you talk, you're very clear with your diction and you emphasise different words, sometimes mimicking an accent, to make a point.

[laughing] That's the thing with acting, you never know which words to stress. You can say it a hundred different ways.

You're not bland...

Yeah, I would go along with you there.

Reading the book, you seem to have the propensity to fall in love a lot.

Oh, man. Really, how do you get that?! Which bit tells you?!

Pretty much every other page, I would suggest.

Falling in love, oh man, I can't believe you said that. Oh man, oh man! During my 16 year long tour, I had no birds. When can I fit a girlfriend into that weekly schedule? Then the pandemic came, then I wrote the book. I was very susceptible, but maybe Kim Wilde was right when she said I wasn't boyfriend material. I'd like to be boyfriend material, but I don't know whether I am or not.

Do you still hold a torch for Chrissie Hynde?

No. I mean, I like her and everything. Don't hold the torch for her. But I reintroduced I Wish (written about Chrissie) into the set. But now I sing it, and I'm singing it about this girl who took me to the Albert Hall. I've changed it a bit. It's a disease being in love. It's sort of a chemical thing.

The very last thing I'm going to ask is, have you ever been back to the Castle Pub? That was the place where Three Bells In A Row and Swords Of A Thousand Men, were both birthed.

I pass it. Haven't actually been in it for a while. They changed it a bit. It's called the Castle again. It was called the Bailey for a long while, but it's been renamed the Castle. So, no, I don't, but I do see it.

Right. Well, maybe, if you're short of an idea, you've got writer's block, you need to go in there for half an hour, and sink a couple of pints, and...

[laughs] If only it were that easy. Man, that's your recipe. You should publish that. My recipe for a hit song.

It's as simple as that. OK, Ed, I'll let you carry on. Have fun writing that speech and learning your Unwinese.

Thank you, man.

Buy: The Pen Is Mightier: Autobiography of a Punk Rocker

|